Lyman Coleman and I were sitting in his living room, enjoying glasses of iced tea and chatting about the history of the small-group movement. I asked the Serendipity founder and small-group pioneer where he thinks the movement is today. I was shocked by his answer. "'Small groups' means nothing anymore," he said matter-of-factly. It's not that he's bitter. It's not that he's given up on small-group community. It's just that over the years he has seen the term take on meanings that are miles from what Coleman and his cohorts intended when they first invested in the small-group movement decades ago.

We are wise to learn from our past as a small-group movement. "Those who cannot remember the past," said George Santayana, "are condemned to repeat it." This is far from a new concept. The psalm writer Asaph determined to teach the "hidden lessons from our past. . . . We will not hide these truths from our children; we will tell the next generation" (Psalm 78:2–4). I believe the pioneers of the small-group movement can teach quite a bit to small-group adherents today. So let's bring some of the lessons from our past out of hiding.

The Emergence of the Small-Group Movement

To start from the beginning would take us all the way back to creation or at least as far back as Jesus' small group, but you've probably already read and heard about all that. (If not, I'd recommend reading Biblical Foundations for Small-Group Ministry and Community 101.) So let's start in the last century, as the contemporary small-group movement developed.

According to Frank Lincoln Fowler III, the first use of the term "small-group movement" goes back to the 1920s and 1930s, when Calvary Episcopal Church in New York City "utilized several principles central to the eventual proliferation of the small group movement in the church." The next several decades, however, showed little growth of groups in the church. Instead, there was a strong development outside the church in organizations such as Alcoholics Anonymous and parachurch groups such as the Navigators.

"In the early days," Coleman says, "the small-group movement was primarily an underground movement. The established church didn't want anything to do with it. Also, small groups were often an alternative 'watering hole' for those who had become disenchanted with the established church or had been turned away from the church because they didn't have their lives together." Coleman recounts easily and passionately how the idea of small groups was tested in parachurch ministries and other places in the 1940s and 50s, and how it developed through the antiestablishmentarianism of the 1960s at national training labs, Faith at Work conferences, and retreat centers.

An early experiment in small-group community in the local church took place when Church of the Saviour in Washington, D.C., began in 1946. Elizabeth O'Connor, a member of this pioneering church, chronicled the church's beginnings in her book, Call to Commitment.

In this book and other writings from those involved early on, it's obvious that this movement was not about forms, structures, or numbers; it was about a paradigm shift in how the church viewed itself. It was revolutionary in nature—an attempt to restore the dynamic community in the New Testament church. These pioneers wanted to demolish the "edifice complex," transform the insider mentality of many churches, and get away from a purely knowledge-based form of the Christian life. Two major themes in these early days of small groups emerged: (1) commitment (to Christ and one another) and (2) the giving away of one's life, which involved a strong sense of calling and personal surrender.

"This is important for a church to understand," writes O'Connor, "for when it starts to become the church it will constantly be adventuring out into places where there are no tried and tested ways." O'Connor characterized the church of the early- to mid-1960s as an institution in which the pioneering spirit had become foreign. The church that is true to its mission, she said, "will be experimenting, pioneering, blazing new paths, seeking how to speak the reconciling Word of God to its own age. It cannot do this if it is held captive by the structures of another day or is slave to its own structures."

Ralph Neighbour, founder of TOUCH Outreach Ministries, and a strong proponent of the cell-church model, was planting churches in New York at the time and decided to go down to Washington, D.C., to check out Church of the Saviour.

"I saw the people of God operating a coffeehouse where everyone was a minister," he said in an interview I conducted with him. "I began to understand that my theology didn't fit the traditional church. I believed in the priesthood of all believers not just as a token phrase but as the lifestyle of a true believer. I got so frustrated that I said, 'I will not give the rest of my life to this nonsense!'"

Neighbour says this experience launched him on a personal journey that finally broke him out of the entire lifestyle of organized religion. He found a few other men who were similarly convicted, met with them for awhile, and eventually moved to Houston to plant an experimental church consisting of small groups. Though he didn't know what to call it at the time, it's come to be known as the cell church model.

What Drives the Mavericks of the Movement

Coleman portrays himself as a maverick in the Christian-education world of the 1960s, yet during this time, his influence in the church was growing. Ralph Neighbour said he and the other pioneers of the time were "a little rat pack of guys who had a vision and found each other, shared thoughts, and did not worry about copyrights."

Like Coleman, Neighbour bristles at the use of the term, "small groups," which he calls "a tepid term that theologically has absolutely no teeth." The issue these pioneers have with the term "small groups" is not really the terminology itself, but what they believe small groups have come to represent.

To better understand their perspective, we must understand where these men started. Coleman, for instance, worked with the Billy Graham Crusade in the late 1950s. Along the way, he met Sam Shoemaker, founder of A. A. Coleman says Shoemaker claimed everyone in his community for God. He reached out to prostitutes, drunks, high-society folks, and the down-and-outers.

To understand Neighbour's frustrations with the typical program-based American church, church leaders, and today's small-group movement, you must appreciate his heart and passion that still drives him today at 85 years old. He believes that groups are "Christ's basic bodies," made up of people who see themselves as ministers empowered by the Holy Spirit, and they exist to reap the harvest.

Both of these men are still driven today to see the small-group movement return to its original outward orientation—its missional priority. When either talks about what some churches are doing in this direction, he moves to the edge of his chair and talks with passion. While their physical voices may be starting to weaken, their voice in the small-group movement is strong and clear.

Their concern about small groups and the small-group movement turning inward rather than remaining missional in nature has been a real concern for more than 50 years. In 1967, Donald James, director of the Pittsburg Experiment after the retirement of founder Sam Shoemaker, said, "The biggest danger of the small-group movement is that as individual members begin to get 'changed,' they sometimes tend to form pious cliques that meet only to mirror their own goodness, and under the guise of study withdraw from the world rather than seek to be used by God to become his lights in the darkened situations of our communities."

Church of the Saviour experienced a similar pattern as far back as 1958. They found that, over time, in their initial fellowship groups something happened that was "like the going out of a light." Many people were experiencing a new awakening to Christ, O'Connor says, "but although we maintained strong programs of study and prayer, no group did anything significant in the way of service." O'Connor confesses, "We had ceased to be the Christian Church when we were no longer seeking to give our lives away." So over a period of six weeks, the church transitioned to mission groups. These groups had three functions: to nurture its own members, to serve, and to evangelize. O'Connor clarifies that the structure—whatever it was at the time—was irrelevant. The values and goals of the group were much more important than the structure.

The concerns of those early pioneers started to eventuate in the 1980s and 1990s. Coleman says the church-growth movement at that time hijacked the small-group movement. Thus, small groups took on a new purpose: to close the back door. The idea of small groups being merely an assimilation strategy for the church aggravates Coleman. Neighbour shares the feeling, writing: "If small groups become just another church-growth program that fails to help people experience the presence and power of Christ, they will not effectively train followers of Jesus to become disciples that can make disciples."

Some are beginning to question whether the resources provided to make leading groups easier has made them less effective in their true purposes. Brad Himes, who oversees small groups at Broadway Christian Church in Mattoon, Illinois, says, "It seems that at some point in the late 90s things changed. The VHS/DVD curriculum became popular and small groups began looking like a cookie-cutter ministry where most churches adopted it because that was what other churches had been doing." Himes's church decided to go back to the roots of the small-group movement:

We have been blessed at our church with a husband and wife who were trained by Richard Peace from Serendipity back in the 80s. We have incorporated a modified Serendipity study method for our groups where the leaders are trained to prepare and write the curriculum for each week. We no longer rely on DVD curriculum in these new groups; instead the leaders go through an extensive training program and the groups open up the Bible each week, read God's Word, and the leader facilitates discussion through the passage.

The Stages of Movements

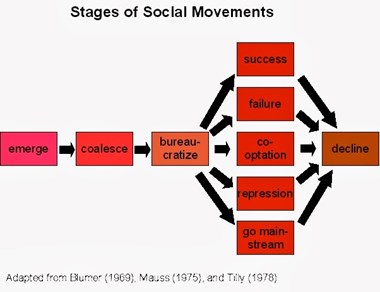

In my discussions with Ralph Neighbour, he passed on insights that he has learned from others about movements. One of those people is Bill Beckham, who has worked closely with Neighbour over the years. It's important to understand movements in order to evaluate where the small-group movement has been and where it is today. Movements typically develop over time in three (or up to about eight, depending on which sociologist you read) levels.

Level 1: Emergence. This is where the movement begins, of course, with pioneers who are often creative geniuses who have a radical passion. They are, as Neighbour shared with me, on-fire, desperate rascals willing to attack the status quo. In the small-group movement, this stage lasted in some form from the 1920s through the 1970s.

Level 2: Coalescence/Synthesis. At this stage, leaders (or managers, as they often are) seek to organize all the chaos of the founders. Neighbour told me that at this stage the tendency is to freeze the fire of the founders. I believe this is also the time when the goals of the founders are apt to change. In "The Stages of Social Movements," Boundless.com reports, "One of the difficulties in studying social movements is that movement success is often ill-defined because the goals of a movement can change." This seems to be particularly true of the small-group movement. Lyman Coleman shared with me how the organizers of the church-growth movement changed the purpose of small groups from reaching the hurting people outside the doors of the church to being a means for closing the back door of the church. In other words, the main audience moved from outsiders to insiders. With that in mind, it appears that the small-group movement went through this stage in the 1980s and 1990s.

Level 3: Bureaucratism. At this stage, systems are set in place that help the movement fit into conventional lifestyles and rituals. This takes place by the establishment of certain rules and procedures within the established culture. Of course, this new bureaucratic system is often the antithesis of what those radical pioneers fought so hard for. The movement can now settle into status quo. Some point to 1991 for the beginning of this stage, when Prepare Your Church for the Future by Carl George was published. It was in this era that a large number of books and magazine articles were published. Everyone wanted to define what small groups were and were not. By 1996, when I founded SmallGroups.com, the small-group movement was becoming mainstream.

After Level 3, movements may go in a number of directions before declining.

So where are we as a movement today? And, more importantly, what does that mean for the future of the movement? Neighbour doesn't mince words. He says we're at Level 3: Bureaucratism, and he calls this stage "cold steel nonsense." Coleman would agree. He talks of how the movement has become more about forms, structures, and numbers than simply reaching the broken people in our world.

Yet these pioneers certainly have not given up on Christ-centered, authentic community. They may not like the bureaucracy that the small-group movement has become, but they have hope for what God can do through it in the future. They stand not only as witnesses to the past but also as cheerleaders encouraging us to throw off everything that hinders and to keep running with perseverance. Moreover, they stand as beacons, pointing us to Jesus, the real pioneer and perfecter of every spiritual movement.

Learning from the Past

So what can small-group ministry leaders learn from the history of the small-group movement? What have these pioneers taught us that can help make the movement stronger today? What should we pass to the next generation of group leaders?

Perhaps the best thing we can do as ministry leaders is step away from our responsibilities for a short while to examine our hearts, our strategies, and our structures. Get away for a day or a weekend and consider why you're doing small-group ministry and what constitutes a win in your context. In other words, think in terms of biblical vision, mission, and purpose. Gather a team—staff or volunteer or both—and prayerfully discuss these big-picture questions.

As you consider the purposes of your small-group ministry, compare them to what the small-group pioneers had in mind. Is your ministry carrying on their hard work? Is your ministry too focused on those already part of the church? Have you lost a sense of all that small groups can do for the kingdom? We can learn quite a bit from these small-group pioneers. In fact, they may be playing the role of prophet for us today. Ultimately, they point us to the real expert on community life: the One who created it.

—Michael C. Mack is a founder of and advisor for SmallGroups.com, author of 14 small-group books and discussion guides, and small-group ministry consultant; copyright 2014 by Christianity Today.